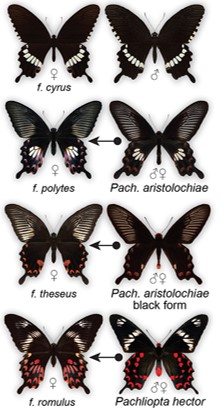

The females of the common mormon, Papilio polytes, mimic inedible butterfly species to avoid predation. But not all females in a population have this property and mimicry is not at all seen in males.

Interestingly, the females of the species are seen to mimic different model species across different populations.

Mimetic forms of Papilio polytes: form cyrus, form polytes and form theseus. Images courtesy Riddhi Deshmukh

What is the mechanism behind the evolution of such polymorphic mimicry, that too only in females?

Krushnamegh Kunte and team from NCBS, Bengaluru, were intrigued. So they collected samples of butterflies that had similar mimetic forms from South Asia, Philippines and Java Solomon Islands and Australia and started experimenting.

These butterflies showed distinct mate preferences and resisted hybridisation. Whole genome sequencing confirmed the divergence of these populations on the phylogeny of these butterflies. The results suggest that mimetic butterflies from Philippines, Java and South Asia are distinct species.

What was common to the mimetic forms of all three species was the inversion of the dsx (doublesex) gene, considered a mimicry supergene. Aligning the dsx inversion breakpoints in the genome sequences of all three species showed that the breakpoints were the same.

A secondary fossil-calibrated phylogeny showed that the three species which show mimetic forms diverged from Papilio protenor about nine to ten million years ago. The researchers determined that the approximate time of origin of mimetic forms in butterflies was about 9.8 million years ago.

The Himalayan Spangle, Papilio protenor

Image: Atanu Bose via Wikimedia Commons

In P. protenor, both males and females are non-mimetic and monomorphic. There was no inversion of the chromosomal segment containing the doublesex gene. The inversion of the dsx gene and the mimicry limited to females is common in five species of butterflies now.

P. alphenor, P. phestus, P. ambrax and the common ancestor of P. polytes, P. javanus diversified about 4.21 million years ago. About 1 million years ago, P. polytes separated from P. javanus. Pachliopta aristolochiae and P. hector diverged from one another around 450 thousand years ago.

The researchers found that the different forms of P. polytes share associated inversion breakpoints. The mimetic polymorphisms could be mapped to dsx alleles. What is the dominance hierarchy of these alleles?

To find out, the researchers crossed pure-breeding lines of different forms. The romulus form of P. polytes which mimics the inedible butterfly species, Pachliopta hector, evolved less than 450 thousand years ago.

The crimson rose, Pachliopta hector

Image: Tarique Sani, via Wikimedia Commons

The alleles in this form are dominant over the polytes form, which evolved earlier, more than 9 million years ago. Similarly, the polytes form, which mimics Pachliopta aristolochiae, exhibits allelic dominance over the non-mimetic cyrus form.

The common rose, Pachliopta aristolochiae

Image: Peellden, via Wikimedia Commons

Interbreeding between various mimetic and non-mimetic forms of Papilio polytes did not break this allelic dominance hierarchy.

“In other words, non-mimetic phenotypes are universally recessive and mimetic phenotypes are universally dominant. Moreover. successive novel mimetic forms have complete dominance over pre-existing forms”, says Riddhi Deshmukh, who has moved on from NCBS Bangalore to the University of Lausanne in Switzerland for her postdoctoral work.

This step-wise evolution of female forms is an example of what is called Haldane’s sieve. The British geneticist, J. B. S. Haldane, pointed out that dominant beneficial alleles would have a higher chance of becoming more common in a population than the recessive ones. The new dominant alleles, which are rare initially, are subjected to directional selection to escape from predation. This leads to a rapid spread of a beneficial mutation through a population. And selective sweeps for fixation reduce genetic variation near that locus. The research team found that dsx alleles in Papilio polytes have signatures of selective sweeps and episodic positive or directional selection.

The integrity of dsx alleles is protected by inversion. The inverted segment does not allow recombination. However, a new mimetic form with intermediate phenotypes between the romulus form and the polytes form has been reported. This intermediate form possesses romulus-like forewings and polytes-like hindwings. Breeding experiments using this intermediate form yielded fertile and genetically stable offspring. The occurrence of this type of intermediate form is attributed to rare genetic exchange between the dsx alleles.

“This intermediate phenotype does not mimic any butterfly that is inedible. So it is not protected from predation. But, if, in some other landscapes, such naturally occurring variations mimic an inedible butterfly, they might become more dominant phenotypes in that landscape”, says Krushnamegh Kunte, NCBS Bangalore.

These findings of Krushnamegh Kunte and team provide insights into how molecular mechanisms shape the evolution of the remarkable diversity of butterflies that show mimicry and mimetic polymorphism.

eLife13:RP101346 (2024);

DOI:10.7554/eLife.101346.1

Reported by Rahul Kumar

Sheodeni Sao College, Magadh University

This report was written during a recent online workshop

for the capacity building of science faculty in India to write science in engaging ways.

The workshop aims to build skills for writing better scientific papers, reviews and project proposals in a systematic manner, starting with simple and proceeding to more complex forms of writing. conducted by scienceandmediaworkshops

The next workshop for science faculty and scientists

will focus on agriculture and allied fields

Leave a comment